Why Measurements on the Edge Require Careful Planning

von Shaun Dustin | Aktualisiert: 05/11/2016 | Kommentare: 1

I have worked with Boy Scouts for the past 18 years. When I need to talk to boys about taking risks, I share a story about three young men who were competing for a job to deliver goods over a mountain pass with hairpin turns and steep cliffs.

It was a dangerous road that called for skill and judgement.

The man doing the hiring had a simple test. He took the candidates up to the road, and asked them how close they could get to the edge of the cliff and still get his trucks and his cargo over the pass.

- The first kid said, “I am such a good driver that I can get so close the tire tracks will be right on the edge.”

- The second kid said, “I am so good that you will only see half the tire track because the other half will be over the edge.”

- The one that got hired said, “I don’t know, but if you hire me, you might need to repaint your truck because I’ll be so far from that cliff that I might be scraping the side of the mountain.”

What does that have to do with instrumentation? Well, sometimes as instrumentation professionals we misunderstand our mandate. We think we have been asked to show what great drivers we are, when really we are being asked to deliver cargo efficiently and safely. We get tempted to push the equipment right to the edge of its capabilities—to drive on the edge of the cliff.

That’s awesome IF:

- I am making the measurement to determine what the limits of the equipment are

- There is no other way to get the data

- It’s my truck and I feel like it

Usually, however, the customer doesn’t care how cool my program is or how close I am to the performance limits of the hardware; they need reliable data that allows them to do their job. The truck owner does not care about the driver’s skill in pushing the equipment; they care about the driver’s skill in delivering the cargo.

We are delivering cargo. In the areas where I work (infrastructure and machine monitoring), people make measurements to mitigate risks. They want to know if the dam is going to wash out and kill people, or if the bridge is going to fall down and kill people, or if the machine is going to blow up and stop the production and put people out of work and an owner out of business.

That risk mitigation is the payload, and making a poor decision about pushing the wrong gear to its limits because I think I can, rather than specifying appropriate equipment operating well within its capabilities, does not solve the customer’s problems. Hardware costs might be marginally higher to do it right—scraping the paint off—but compared to the multi-billion-dollar potential cost of failure, the right approach is obvious.

To measure the extreme events (or worst-case scenarios) that we are usually after, we need equipment that is operating well within its design envelope when those events occur. This is pretty obvious and easy when we talk about factors such as temperature stability or watertightness, but it gets more complicated when we start talking about sampling rates or accuracy or precision—especially with customers new to electronic data collection who have not had the experience of figuring out how to make decisions or draw conclusions from inadequate data. It is our job to evaluate and mitigate those risks.

The Middle and the Edges

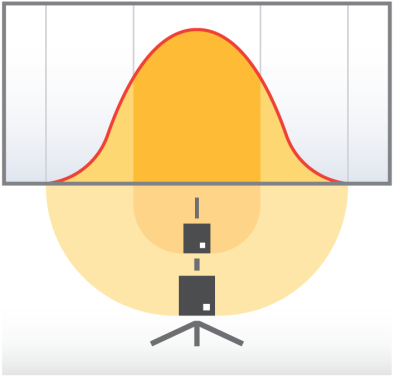

In performance monitoring, if the behavior of the system we are monitoring is represented by a normal distribution, I am generally not all that interested in what’s going on in the middle of the distribution. It is cool and all, but what I really put the sensors out there for is so that I can know if I start moving towards the edges. The stuff at the high and low ranges of the instruments is what I am after—not the easy stuff in the middle.

So why would I specify the system to be excellent in the middle and then push the envelope at the edges where the important data are? I see this a lot, especially when we start talking about dynamic measurements. We specify the cheapest possible equipment that might work in the range where we need it, which then pushes the channel count, speed, and power right out to the edge of the capability of the machinery. Now we’ve compounded the risk of failure of the primary system by adding the risk that our measurement system will fail too. If you care about the data on the edge, if you care about those extremes, it’s imperative to design the system to work comfortably at those extremes.

When we make a measurement, the reason is not to test the capabilities of the electronics so we can beat our chests and brag about how close we got to the edge of the cliff. Rather, it’s about getting the best data that we can so that we can make the best decisions that we can. And we don’t do that by implementing a system that just barely makes the grade. We do that by understanding what is really important to the customer, and doing that job.

Equipment Made for Your Extremes

When you are planning your system, consider the measurements that are important to you. Review the specifications of the equipment you are considering to ensure it will provide you with good data at your extremes—whatever they may be for your particular application. At Campbell Scientific, our core focus is to help you make the best measurement possible. We do this by designing and manufacturing high-quality equipment, and then helping you design your system. To get help selecting the appropriate equipment for your system, contact us or complete our Ask a Question form.

Dr. Shaun Dustin was a registered professional civil engineer and led the Geotechnical and Structural Instrumentation Group at Campbell Scientific, Inc. He worked on projects ranging from 3-Mile Island to Space Mountain, but his favorite thing to do—besides spending time with his family—was solving problems that matter. .

Dr. Shaun Dustin was a registered professional civil engineer and led the Geotechnical and Structural Instrumentation Group at Campbell Scientific, Inc. He worked on projects ranging from 3-Mile Island to Space Mountain, but his favorite thing to do—besides spending time with his family—was solving problems that matter. .

Kommentare

Fuwei.Jin | 05/12/2016 at 08:47 AM

Just as Dr. Shaun said, a true engineer should think over responsibility he/she will undertake in project, challedge is not how to get data effectively and economically, but data's representativeness and reliability. Wish our project designers and system integraters can pay more attention about their cargo instead of their skill......

Please log in or register to comment.